Latest updates on country situation

23 September 2025

By September 2025, around 1.2 million children, nearly 46% of the school-age population in Tigray, were out of school, according to the regional Bureau of Education, largely due to the lingering social and economic impacts of the war. Nationwide, more than 8.3 million children were out of school by June 2025, driven by conflict, displacement, climate shocks, and insecurity. The prolonged lack of educational access has heightened protection risks, leaving children increasingly vulnerable to early marriage, hazardous labour such as mining, and unsafe, irregular migration. (AS 19/09/2025, UNICEF 02/01/2025, TR 22/02/2025, Education Cluster accessed 25/09/2025)

26 August 2025

Communities in Tselemti (North Western zone) and Kola Temben (Central zone) woredas of Tigray are facing worsening conditions as prolonged drought compounds the impact of the 2020–2022 conflict. Media reports suggest nearly 50,000 people in Tselemti are struggling with hunger and displacement, with more than 9,000 livestock lost. In Kola Temben, at least 22 people and over 27,000 livestock are reported dead based on unverified figures. Alarming malnutrition levels linked to failed harvests further aggravate the situation. Proxy global acute malnutrition rates have reached 62% among children under five and over 70% among pregnant and lactating women, heightened by limited health and nutrition services. Forecasts for the October–December Deyr season point to below-average rainfall across much of the Horn of Africa. If this materialises in northern Ethiopia, drought conditions are likely to persist into early 2026, prolonging already critical humanitarian needs. (AS 19/08/2025, ECHO 14/08/2025, ICPAC 26/08/2025)

10 June 2025

In late May 2025, escalating armed violence by non-state armed groups in the border areas of Oromia and Benishangul-Gumuz regions of Ethiopia displaced over 11,000 people. This violence, driven by political and ethnic tensions, has severely affected communities in Harowata kebele of Sasiga district (Oromia region), displacing approximately 5,500 people. At the same time, the attacks have forced around 5,900 people in Kamashi zone (Benishangul-Gumuz region) to flee. An attack on 20 May in Mizyiga, Kamashi zone (Benishangul-Gumuz region), resulted in at least 16 casualties, abductions, and arson. Some of the displaced are seeking shelter in government buildings. Their priority needs include food assistance, NFIs, and protection services. (ECHO 06/06/2025, Protection Cluster 10/06/2025, The Reporter 24/05/2025)

08 April 2025

Between January–February 2025, an estimated 1,200 people fled to North Western zone from various zones in Tigray region because of insecurity and fear of conflict, illustrating continued population movement. These newly displaced people add to the more than 750,000 people who were internally displaced across Tigray in August 2024. The continued arrival of displaced people aggravates an already dire situation. These individuals live in poor conditions within collective sites, particularly in schools and makeshift shelters, that are often overcrowded, putting pressure on limited resources and further challenging their wellbeing. The situation raises health and protection concerns for them and strains the relationship between the host community and IDPs, as residents experience disruptions to essential services, especially education, with many displaced individuals sheltering in schools. The primary needs identified include shelter, livelihood, food and NFIs, health, and WASH services. (GSC 04/04/2025, UNHCR 28/02/2025, IOM 21/02/2025)

01 April 2025

In the 2024–2025 academic year, more than 7.2 million students across Ethiopia have been unable to attend school owing to conflict and insecurity. Amhara region is the hardest hit, with over 3,600 schools already closed and 4.5 million students out of school. This is an increase of over 500,000 students since October 2023, when approximately 3.9 million primary and secondary students were out of school in the region. Attacks have targeted educational infrastructure, while teachers and school administrators have faced threats, detention, and even killings, further disrupting education and making it unsafe for learning to continue. Fano militia have also previously ordered schools to close and demanded ransom for kidnapped teachers. (AS 31/03/2025, African Perceptions 25/03/2025, NDTV 24/01/2025)

11 February 2025

By 6 February 2025, the resurgence of cholera in Amhara region had produced over 160 cases and killed three. Of these, 125 cases and two deaths occurred in West Gondar zone, three cases and one death in Central Gondar, and 33 cases in Bahir Dar, the region’s capital. Humanitarian access restrictions from armed conflict in the region will likely hinder the response. (ECHO 06/02/2025, AS 07/02/2025)

14 January 2025

Since October 2024, seismic activity has been affecting parts of the Afar and Oromia regions, particularly the Awash and Dulecha districts. This activity intensified at the end of December, with approximately 50 earthquakes recorded between 4–10 January 2025, ranging in magnitude from 4.2–5.8. The strongest quake occurred near Dofen Mountain on 4 January. Approximately 51,000 people have been displaced in the Afar Region, and 20,000 in the Oromia Region. The majority of IDPs have sought refuge in informal sites, including schools and other facilities. Infrastructure has also suffered damage. Several schools in both regions were severely or partially damaged, affecting over 7,000 students. Widening fissures have disrupted road networks, complicating the transportation of essential supplies. Despite the humanitarian efforts, there remains a critical need for shelter, food, medicine, NFIs, and protection. Scientific assessments are in progress, as it is uncertain if the seismic activity will continue. (OCHA 10/01/2025, ECHO 10/01/2025)

current crises

in

Ethiopia

These crises have been identified through the INFORM Severity Index, a tool for measuring and comparing the severity of humanitarian crises globally.

ETH006 - Conflict, Climatic and Economic shocks

Last updated 27/01/2026

Drivers

Conflict/ Violence

Floods

Drought/drier conditions

Political/economic crisis

Crisis level

Country

Severity level

4.2 Very High

Access constraints

5.0

ETH001 - Multiple crises

Last updated 27/01/2026

Drivers

International Displacement

Conflict/ Violence

Drought/drier conditions

Floods

Political/economic crisis

Crisis level

Country

Severity level

4.3 Very High

Access constraints

5.0

ETH003 - International Displacement

Last updated 27/01/2026

Drivers

International Displacement

Crisis level

Country

Severity level

3.1 High

Access constraints

4.0

Analysis products

on

Ethiopia

15 July 2025

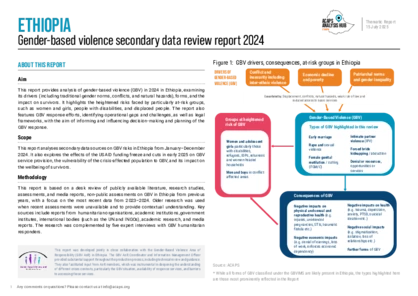

Ethiopia: gender-based violence secondary data review report 2024

DOCUMENT / PDF / 867 KB

This report provides analysis of gender-based violence (GBV) in 2024 in Ethiopia, examining its drivers (including traditional gender norms, conflicts, and natural hazards), forms, and the impact on survivors.

13 March 2025

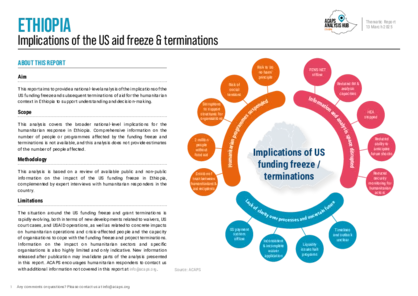

Ethiopia: implications of the US aid freeze & terminations

DOCUMENT / PDF / 1 MB

This report aims to provide a national-level analysis of the implications of the US funding freeze and subsequent terminations of aid for the humanitarian context in Ethiopia to support understanding and decision-making.

Attached resources

05 July 2024

Ethiopia: situation and needs of Sudanese refugees in Amhara region

DOCUMENT / PDF / 529 KB

This report analyses the humanitarian needs of Sudanese refugees hosted at the Kumer and Awlala refugee camps, those who left and are sheltering outside, and the factors aggravating the situation in order to support humanitarian decision-making.

Attached resources

18 January 2024

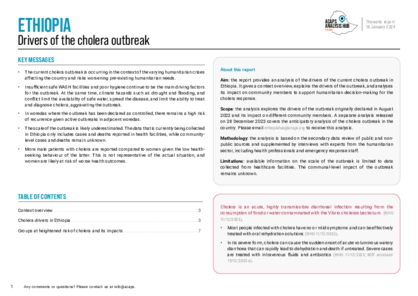

Ethiopia: drivers of the cholera outbreak

DOCUMENT / PDF / 1 MB

The report provides an analysis of the drivers of the current cholera outbreak in Ethiopia. It gives a context overview, explains the drivers of the outbreak, and analyses its impact on community members to support humanitarian decision-making for the cholera response.

02 November 2023

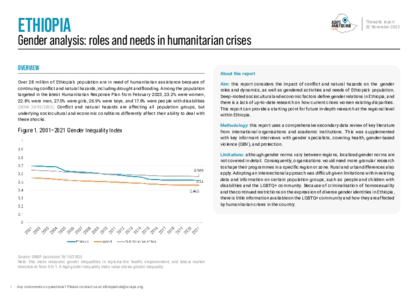

Ethiopia: gender analysis on roles and needs in humanitarian crises

DOCUMENT / PDF / 576 KB

This report considers the impact of conflict and natural hazards on the gender roles and dynamics, as well as gendered activities and needs of Ethiopia’s population. Deep-rooted sociocultural and economic factors define gender relations in Ethiopia, and there is a lack of up-to-date research on how current crises worsen existing disparities. This report can provide a starting point for future in-depth research at the regional level within Ethiopia.